MWT Book Extract - Governance, Hierarchy, and the Delivery Architect

Unavoidable Hierarchy of Responsibility

Hierarchies are powerful organising constructs. One of the assumptions people often make about the MWT Model is that if it is market-based it must also be against hierarchical organisation. This is not true as hierarchical organisation is an important feature of corporate governance. Without the overriding principle that the CEO and Board are ultimately responsible for the organisation’s performance (and the organisation's overall impact on society) there can be no corporate governance. The unavoidable hierarchy of responsibility draws a line from each employee, through their managers, directly to the Board.

It is the unflinching burden of this hierarchy of responsibility that often causes the best-seller lists for management books to be dominated by what are essentially self-help books for people in positions of power and responsibility. Indeed, much of the management profession has been developed to push this burden of responsibility down the hierarchy. This is different to delegation. Delegation, or rather the correct distribution of decision rights, is by definition always a positive contribution to the organisation’s effectiveness. Distribution of decision rights is in fact enabled through the hierarchy of responsibility. If a manager is ultimately responsible regardless of delegations then there is no point restating the managers responsibilities and calling it management. This is what subtlety occurs with Single Point Management (see Chapter xxx). In a sense, when I say 'management is the process of determining which decisions don't have to be made by consensus' I am also saying that management is the process of determining which decisions don't have to be made by the manager.

Management should always involve the organised delegation of responsibilities. You will often hear that you can delegate responsibility but not accountability (or something like that). This management truism is indeed true. What it is saying is that the manager is always accountability even though they have given the task to somebody else. The problem arrises when the one class within an organisation (in this case that class is the management class) has both the right to delegate and the right to judge capability. This violates the MWT principle to ‘make management one step removed from measurement’. Too often I have seen managers attribute their failure to 'unskilled resources' and too often this is the case when those same resources have been working for the manager for months or even years. Though not always the case in well matrixed organisations and project, managers are responsible for the capabilities of their people – so blaming your resources for failure is not an option.

Market-based management partially solves this problem by providing mechanisms for people to choose their managers. However, this is not an ideal solution as it will mean that truly challenging endeavours will never be resourced. Also, as discussed in Chapter xxx, competitive differentiation and alignment to strategy would be ineffective under a strictly market-based management model. In order to resource truly difficult endeavours and maintain a strategy of differentiation, you have to strictly follow the rule that if a subordinate is responsible then the manager is also responsible.

Due credit should be given to organisations who try to solve this governance problem with such mechanisms as '360 degree' assessments and other elements of a comprehensive performance management processes. In fact, even the very existence of a human resources department is supposed to provide a mechanism for resolving problems with managers who have taken advantage of the largely political relationship between the manager and the managed which allows their own failings to be exploited and reframed as leadership. However, the problem with 360 degree assessment and reliance on a separate human resources department is that these involve interventions. As mentioned in Chapter xxx, any management model which relies on interventions cannot improve corporate governance because managers control resource allocation and therefore they control which interventions are resourced. So in effect they control which interventions occur. If those resource allocations are ineffective (from the organisations perspective) the interventions simply wont occur and the risks to effective corporate governance will not be managed.

The New MWT Hierarchy

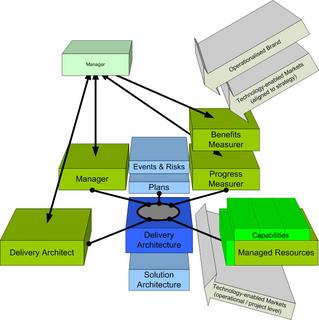

The New MWT Hierarchy reinforces the idea of an unavoidable hierarchy of responsibility. More importantly is provides a more comprehensive explanation of the forces which are already acting within the management hierarchy. The New MWT Hierarchy should be considered a management pattern (in the sense of Christopher Alexander's A Pattern Language as discussed in Chapter xxx). In the diagram for this pattern each of the olive green components are a different person performing a different role. It is important that these are physically different people. It is only then that the correct incentives are in place for the pattern to work.

However, some will correctly note that this is overkill for smaller organisations or projects. It is true that this pattern evolves too many people to be suitable for small organisations. However, it does more effectively represent the forces which need to be in place to govern the hierarchy. It is only because the risks are smaller in smaller organisations that roles can be combined into less resources. It may even be possible that the roles are combined into a single manager. This is of course exactly what the traditional view of a management hierarchy would suggest. But I believe that in all cases where the roles are combined a risk is introduced. It is only because management practices have developed an unquestioned value proposition unto themselves that this idea of risk management within the management model will be unintuitive to many. This is why risk management within the management model is such an important component of the MWT Model.

Note also that it is not just the size of the organisation that indicates the roles should be separated into different people. Other risks such as the combining of diverse capabilities with a new collaboration / delivery architecture also indicate that separate people in each role should be used. Also, any time when an independent project management firm is used to manage other firms the roles should be separate people (or perhaps separate firms).

It might also be the case that a strong general manager will require a separate delivery architect to supplement their general management skills with domain or task-specific skills. There is a long standing argument about whether a good manager can manage anything. The answer to this is 'it depends'. An understand of The New MWT Hierarchy allows the decision to be made by assessment of the managers skills in relation to the domains they are managing. The discussion on the relationship between the manager and delivery architect will make that clear.

The individual components of the diagram are introduced in the section below. As for all MWT collaboration architectures (as The New MWT Hierarchy is simply a generic collaboration architecture) in addition to the component descriptions a set of traversals across components will also be provided.

<--- continued --->

Hierarchies are powerful organising constructs. One of the assumptions people often make about the MWT Model is that if it is market-based it must also be against hierarchical organisation. This is not true as hierarchical organisation is an important feature of corporate governance. Without the overriding principle that the CEO and Board are ultimately responsible for the organisation’s performance (and the organisation's overall impact on society) there can be no corporate governance. The unavoidable hierarchy of responsibility draws a line from each employee, through their managers, directly to the Board.

It is the unflinching burden of this hierarchy of responsibility that often causes the best-seller lists for management books to be dominated by what are essentially self-help books for people in positions of power and responsibility. Indeed, much of the management profession has been developed to push this burden of responsibility down the hierarchy. This is different to delegation. Delegation, or rather the correct distribution of decision rights, is by definition always a positive contribution to the organisation’s effectiveness. Distribution of decision rights is in fact enabled through the hierarchy of responsibility. If a manager is ultimately responsible regardless of delegations then there is no point restating the managers responsibilities and calling it management. This is what subtlety occurs with Single Point Management (see Chapter xxx). In a sense, when I say 'management is the process of determining which decisions don't have to be made by consensus' I am also saying that management is the process of determining which decisions don't have to be made by the manager.

Management should always involve the organised delegation of responsibilities. You will often hear that you can delegate responsibility but not accountability (or something like that). This management truism is indeed true. What it is saying is that the manager is always accountability even though they have given the task to somebody else. The problem arrises when the one class within an organisation (in this case that class is the management class) has both the right to delegate and the right to judge capability. This violates the MWT principle to ‘make management one step removed from measurement’. Too often I have seen managers attribute their failure to 'unskilled resources' and too often this is the case when those same resources have been working for the manager for months or even years. Though not always the case in well matrixed organisations and project, managers are responsible for the capabilities of their people – so blaming your resources for failure is not an option.

Market-based management partially solves this problem by providing mechanisms for people to choose their managers. However, this is not an ideal solution as it will mean that truly challenging endeavours will never be resourced. Also, as discussed in Chapter xxx, competitive differentiation and alignment to strategy would be ineffective under a strictly market-based management model. In order to resource truly difficult endeavours and maintain a strategy of differentiation, you have to strictly follow the rule that if a subordinate is responsible then the manager is also responsible.

Due credit should be given to organisations who try to solve this governance problem with such mechanisms as '360 degree' assessments and other elements of a comprehensive performance management processes. In fact, even the very existence of a human resources department is supposed to provide a mechanism for resolving problems with managers who have taken advantage of the largely political relationship between the manager and the managed which allows their own failings to be exploited and reframed as leadership. However, the problem with 360 degree assessment and reliance on a separate human resources department is that these involve interventions. As mentioned in Chapter xxx, any management model which relies on interventions cannot improve corporate governance because managers control resource allocation and therefore they control which interventions are resourced. So in effect they control which interventions occur. If those resource allocations are ineffective (from the organisations perspective) the interventions simply wont occur and the risks to effective corporate governance will not be managed.

The New MWT Hierarchy

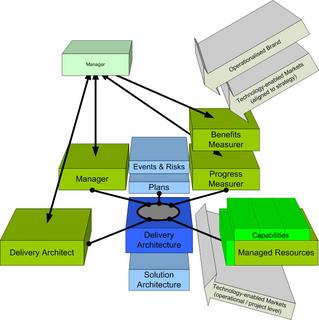

The New MWT Hierarchy reinforces the idea of an unavoidable hierarchy of responsibility. More importantly is provides a more comprehensive explanation of the forces which are already acting within the management hierarchy. The New MWT Hierarchy should be considered a management pattern (in the sense of Christopher Alexander's A Pattern Language as discussed in Chapter xxx). In the diagram for this pattern each of the olive green components are a different person performing a different role. It is important that these are physically different people. It is only then that the correct incentives are in place for the pattern to work.

However, some will correctly note that this is overkill for smaller organisations or projects. It is true that this pattern evolves too many people to be suitable for small organisations. However, it does more effectively represent the forces which need to be in place to govern the hierarchy. It is only because the risks are smaller in smaller organisations that roles can be combined into less resources. It may even be possible that the roles are combined into a single manager. This is of course exactly what the traditional view of a management hierarchy would suggest. But I believe that in all cases where the roles are combined a risk is introduced. It is only because management practices have developed an unquestioned value proposition unto themselves that this idea of risk management within the management model will be unintuitive to many. This is why risk management within the management model is such an important component of the MWT Model.

Note also that it is not just the size of the organisation that indicates the roles should be separated into different people. Other risks such as the combining of diverse capabilities with a new collaboration / delivery architecture also indicate that separate people in each role should be used. Also, any time when an independent project management firm is used to manage other firms the roles should be separate people (or perhaps separate firms).

It might also be the case that a strong general manager will require a separate delivery architect to supplement their general management skills with domain or task-specific skills. There is a long standing argument about whether a good manager can manage anything. The answer to this is 'it depends'. An understand of The New MWT Hierarchy allows the decision to be made by assessment of the managers skills in relation to the domains they are managing. The discussion on the relationship between the manager and delivery architect will make that clear.

The individual components of the diagram are introduced in the section below. As for all MWT collaboration architectures (as The New MWT Hierarchy is simply a generic collaboration architecture) in addition to the component descriptions a set of traversals across components will also be provided.

<--- continued --->

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home